Label Making

Acknowledging complex realities and avoiding snap judgements.

I’ve set alarms to wake up every thirty minutes throughout the night to make sure I didn’t miss any texts or calls from a friend going through a dark place.

I’ve ended numerous relationships out of nowhere in cruel, deeply hurtful ways.

I’ve been a shoulder to cry on again and again, as someone who can just listen and provide a judgment-free space.

I’ve been the annoying drunk guy at the bar hitting on your friend despite her giving clear indications that she’s not interested.

From the time I took my first standardized test, I’ve been told how smart I am.

Only in the last few years have I finally developed some actual emotional intelligence.

I’m a complex person. I have a history of doing admirable and inspiring things. I have a history of callousness, substance abuse, and complete disregard for the feelings of others. I look back at my life thus far and feel tremendous amounts of both pride and shame.

Why am I sharing this? Especially sharing things I still feel ashamed of?

Because I need to acknowledge and accept the full messiness of my reality and my past actions if I want to do better in the future. Here’s why:

Only the Good, Please

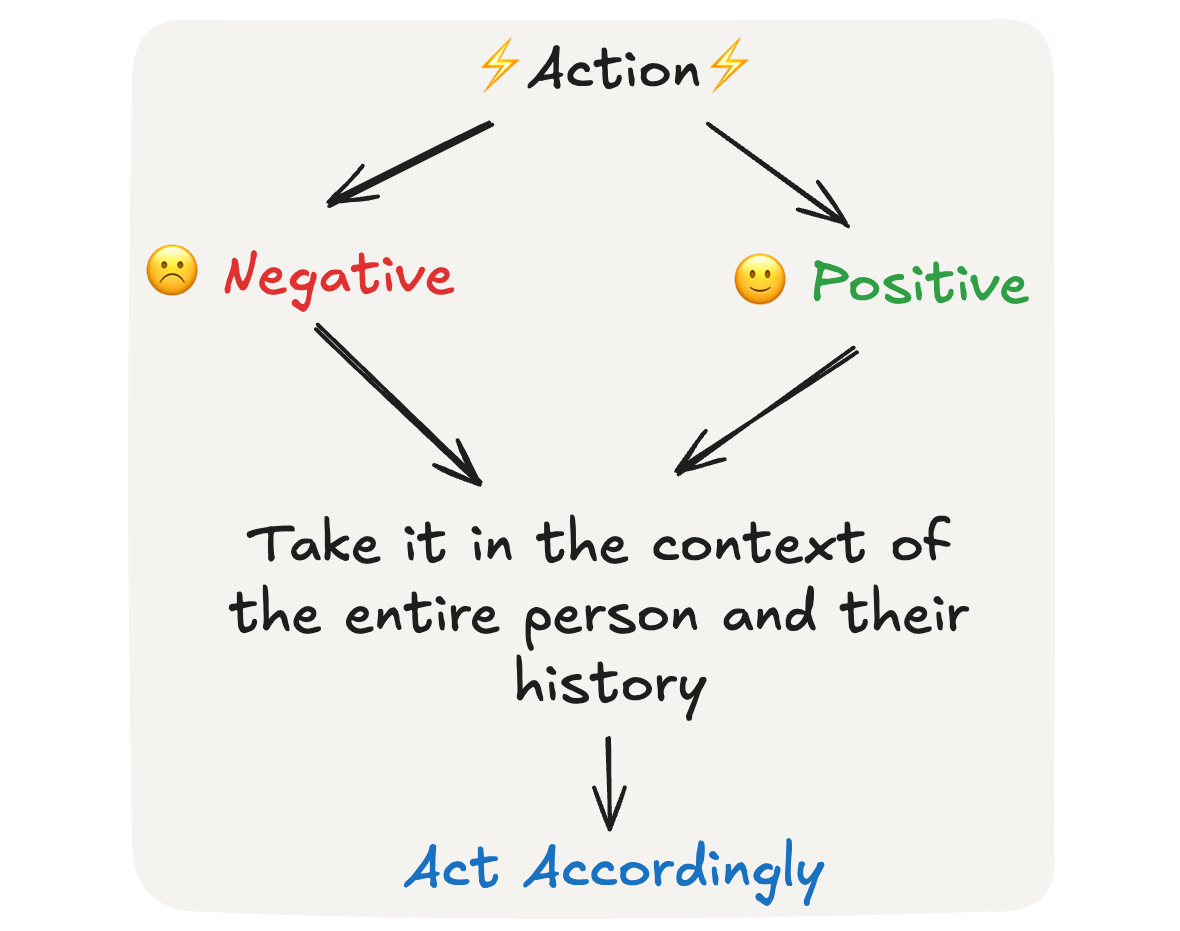

Let’s start with a breakdown of a healthy way to respond after doing something positive or negative:

Negative actions result in acceptance and accountability, and a reduced chance of repeating that action in the future. Positive actions generate positive reactions, and are generally reinforced.

This is very much not the process I’ve spent most of my life following.

After a childhood full of being told I was a good kid – a smart and well-behaved student, kind and caring – being good became my identity. Not just something I aspired to, not something I was on most days, but my entire identity. So when I made a mistake, when I did something negative or outside of my values, I didn’t take a step back, I didn’t apologize and ask myself how I could avoid doing that thing again. I either made up stories for why it wasn’t my fault or ignored it completely. I built up a wall preventing me from getting to the recognition phase, let alone to acceptance or accountability.

I did not see myself as a decent person who was capable of making mistakes that I needed to learn from. I saw myself as a good person, and admitting to mistakes was to admit that my entire precarious self-image might be flawed. I excelled at creating justifications, and was terrible at taking accountability.

So I leaned – hard – into what I was good at. Family asking me how I was doing over the holidays? I could talk for hours about how well I was doing at work, the latest promotion, the fascinating project I was working on. No mention of my rapidly escalating issues with alcohol, my ongoing tendency of getting drunk and playing video games by myself every night of the week. I was the good guy, only doing good things in life, and I wasn’t going to admit otherwise to myself, let alone anyone else.

For me, the process looked more like this:

When I was at the height of my drinking, I fought desperately to keep seeing myself as not straying outside of the good category. If I couldn’t fully remember the previous night’s events, I might preemptively text, “Hey sorry if I was a little crazy last night, those beers were strong!”, when I really should’ve been asking for an honest reality check on just how frustrating I had been to be around. I needed to understand the full extent of the impact my actions had on others, but I couldn’t bear the rupture of identity that might’ve entailed.

I needed to understand myself as a complex and messy human – capable of a full range of actions, both good and bad – in order to take accountability for myself, instead of living in a world of justifications and forced ignorance.

Naughty & Nice Bucket List

Similarly to how I can short-circuit my reaction to doing something negative, we often do the same when interacting with others.

Back in highschool, a girlfriend attempted to share with me how abusive her dad was. My immediate reaction was “Oh it can’t be that bad, he means well.” I cringe thinking about that now, but back then I had met her dad, and he was friendly, funny. I couldn’t envision him having a dark side. I had labeled him as a good person, so I (very incorrectly) assumed my girlfriend must have been overreacting.

Earlier this year I found myself extremely quick to apply a negative label to a new colleague who showed up late to his first big meeting. We had rules and he wasn’t following them, so I slapped on an immediate judgment.

I was following this very common process:

See someone do something you disagree with? That must be a bad person! See someone do something kind? They must be a saint!

I built cholera treatment centers in Haiti amidst an outbreak. I didn’t once make the twenty minute drive to go to see my grandma when she was dying. If I can be complicated, capable of doing a wide range of both good and bad things, perhaps others can as well.

Can the person who just monopolized a group conversation be capable of careful listening, when they’re not so worried about fitting in?

Can the driver who just cut me off in traffic be an incredibly kind neighbor, when they’re not worried about being late to work?

Can the annoying guy at the bar be a great and caring friend, when he’s not letting alcohol strip away all his empathy?

Perhaps instead of immediately slapping a label on someone, we consider an alternative:

We’re all complex. We’ve done kind and cruel things. Simplistic labels prevent us from getting into our messy, complicated, contradictory realities – where our lives are actually lived.

This got me reflecting on society's obsession with cancel culture and how one misstep is often the end of someone's reputation despite decades of actions speaking to their true character. I think there's a lot of love for our fellow human to be found in being able to slow down and take in even a bit more context before making such a black/white/good/bad judgement.

Watching the Olympics made me look up this article on our excessive focus on high performance cultivation starting at early age:

"Performance expectations have a high cost when they’re perceived as excessive - young people internalize those expectations and depend on them for their self-esteem. And when they fail to meet them, as they invariably will, they’ll be critical of themselves for not matching up. To compensate, they strive to be perfect.”